The answer isn’t predetermined; it depends on how individuals and leaders respond. Some will expand. Some will narrow. Most will face a quiet turning point: continue thinking the way they always have or cultivate the cognitive range that the next era of work quietly demands.

This is not a prediction; it’s an invitation. The conditions around us are changing. The question is whether we will.

“AI is accelerating faster than humans can absorb. The only sustainable advantage now is how well you think … not how much you know.”

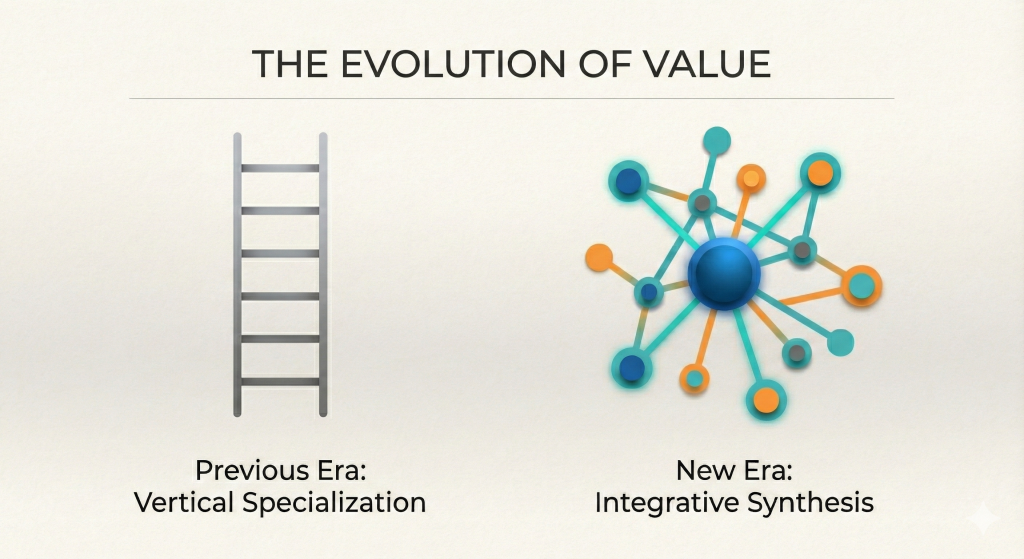

The new year presents an inflection point for individuals and organizations alike. For more than a century, professional advancement rested on a stable assumption: expertise was the primary currency of value. Careers were built through the progressive accumulation of knowledge, mastery of a defined discipline, and the gradual acquisition of experience. This model shaped everything from hiring to development to organizational design. It also reflected the realities of the industrial and information economies, where specialization offered efficiency, predictability, and competitive advantage.

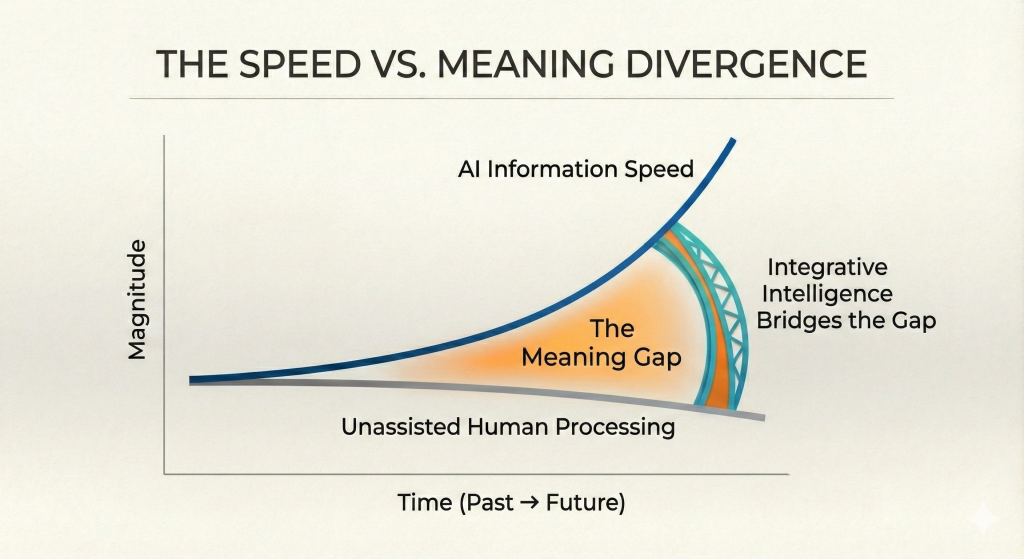

Advancing technology and artificial intelligence are now challenging that architecture. Technologies capable of analyzing data, synthesizing research, generating written and visual content, and modeling strategic decisions have compressed learning cycles that once took years to develop. Tasks that previously distinguished experts from novices can be performed by systems that work at scale, at speed, and without fatigue. As a result, the differentiators that once defined professional value are shifting. The question is no longer how much an individual knows, but how effectively that individual can think, how they interpret new information, integrate disparate insights, and make sense of situations for which no established precedent exists.

This shift is not unprecedented. Throughout history, moments of technological acceleration have been accompanied by cognitive expansion. During the Renaissance, value migrated from narrow specialization toward interdisciplinary capability. Thinkers who could connect ideas across domains such as science, art, mathematics, and language were uniquely equipped to generate new forms of insight. A similar migration is underway today. What appears to be a technological revolution is, at its core, a cognitive one: a transition from an expertise-based economy to an integration-based one. The implications extend beyond technical skill; they touch identity, capability, and the design of human systems.

The Compression of Expertise and the Rise of Interpretation

Artificial intelligence has not eliminated the need for expertise, but it has altered its function. Knowledge that once required lengthy periods of study and apprenticeship can now be accessed instantaneously. AI can summarize research, draft legal text, produce financial modeling scenarios, and generate creative prototypes. This does not diminish the importance of human capability; it changes the nature of its contribution.

Expertise today is necessary but insufficient. Its differentiating potential has weakened not because knowledge has lost value, but because access has expanded. In many settings, the primary bottleneck is no longer information scarcity; it is interpretive capacity. The flood of available data increases the premium on clarity, discernment, and judgment, capabilities that remain uniquely human.

Daniel Pink anticipated this transition in A Whole New Mind, arguing that the economy would eventually elevate abilities such as synthesis, empathy, narrative thinking, and creative design. At the time, these ideas appeared aspirational. AI has rendered them practical. The skills that resist automation are not those rooted in information recall but those rooted in meaning-making. Individuals who can integrate logic and imagination, analysis and interpretation, pattern and context will define the next era of human capability.

“The scarcest resource in the modern economy is not information…it is interpretation.”

Why Fixed Cognitive Identities No Longer Serve Individuals or Organizations

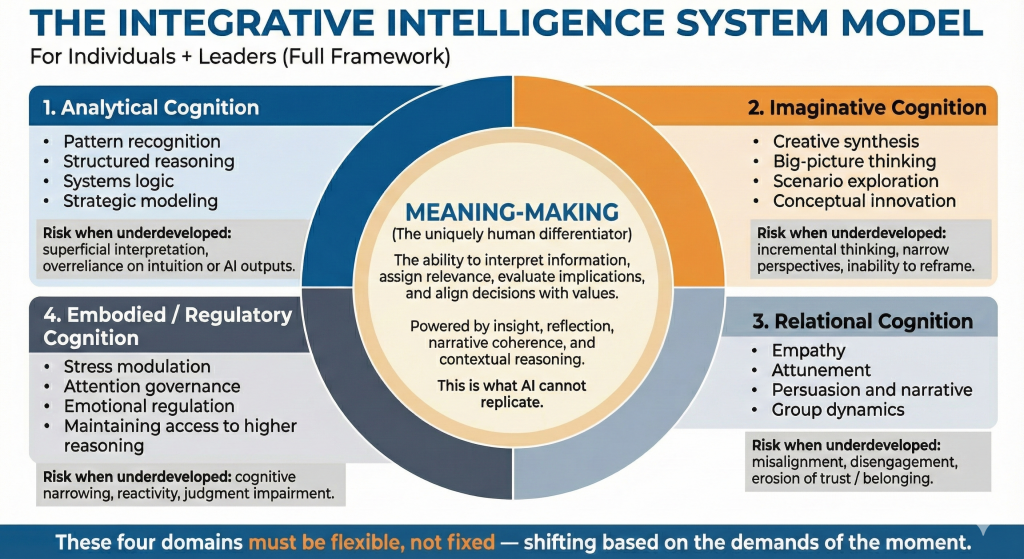

For decades, organizations relied on simplified cognitive labels such as analytical, creative, strategic, and relational, as if individuals possessed stable, singular modes of thought. These categories shaped performance evaluations, team composition, and professional identity. Yet neuroscience demonstrates that such labels are both reductive and limiting. Human cognition is dynamic, multidimensional, and trainable. The adult brain continually reorganizes itself, forming new pathways in response to experience, physical movement, and environmental demands.

This malleability matters in an era of accelerating complexity. Individuals who define themselves by narrow cognitive identities risk constraining their adaptability. The modern workplace demands flexibility: the ability to zoom out and zoom in, to reason analytically and imagine creatively, to interpret emotional cues and assess systemic patterns. Cognition cannot be segmented into rigid compartments without restricting the range of responses available under pressure.

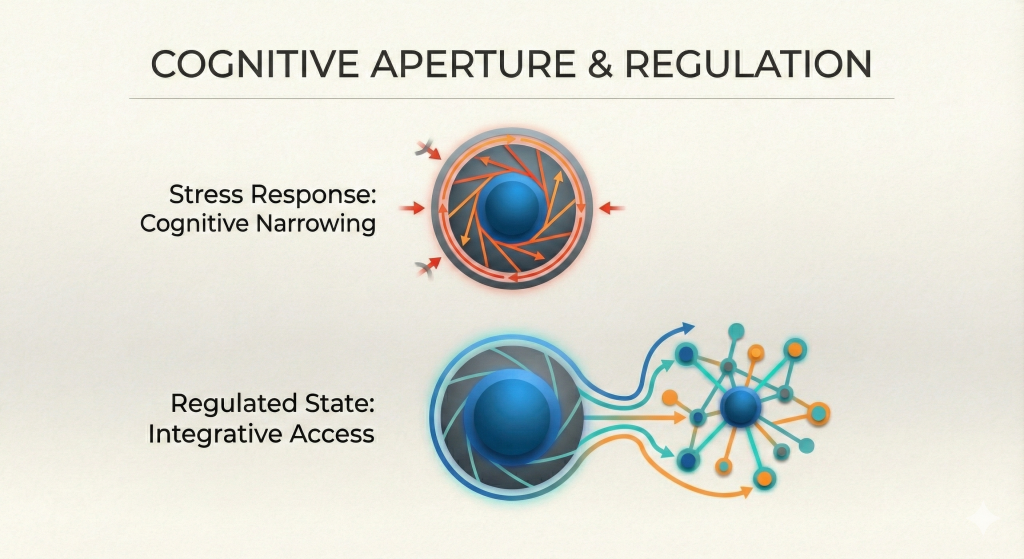

Stress compounds the issue. When individuals experience elevated stress, the prefrontal cortex, the center responsible for reasoning, planning, and creativity, becomes impaired. Under pressure, people do not lose intelligence; they lose access to it. This narrowing of cognition explains why even competent professionals revert to habitual patterns during disruption. They analyze excessively, act prematurely, avoid decisions, or overassert control. These responses reflect a loss of cognitive range, not a loss of skill.

Organizations often mistake these behaviors for deficiencies in competence rather than signals of overwhelmed cognitive systems. Without addressing the underlying dynamics, performance interventions remain superficial. The challenge is not simply to increase capability, but to expand access to it.

“Leaders must manage mindsets with the same rigor they apply to strategy.”

Integrative Intelligence as a Modern Capability

The shift toward an integration-based economy requires a corresponding shift in individual capability. Integrative intelligence is the capacity to synthesize, contextualize, interpret, and adapt across multiple modes of thought. It is not equivalent to being a generalist or a polymath. Instead, it reflects the ability to move fluidly across cognitive domains—analytical, imaginative, relational, and strategic, based on the demands of the moment.

This capacity aligns with a broader transition from what Pink termed the Information Age to the Conceptual Age. As technology assumes more of the routine and analytical components of work, the competitive advantage of humans lies in their ability to perform higher-level operations: asking the right questions, determining relevance, anticipating second-order effects, and constructing meaning where none is immediately apparent.

Integrative intelligence draws upon multiple cognitive mechanisms. Pattern recognition enables individuals to detect relationships across ideas that appear unrelated. Reflective judgment allows for the evaluation of competing interpretations. Emotional regulation enables broader thinking under pressure. Embodied cognition, supported by movement, sensory interaction, and environmental engagement, strengthens neural integration. Together, these factors contribute to a broader cognitive range that is increasingly essential for navigating complex environments.

The Renaissance analogy is useful not as a metaphor, but as a historical precedent. Periods of multidisciplinary integration tend to produce outsized breakthroughs. Today’s environment requires a similar orientation, not because the world demands more eclecticism, but because it demands more coherence.

The Risks of Cognitive Contraction in an Accelerated Environment

When individuals or leaders fail to adapt to this shift, predictable forms of decline emerge. These patterns echo those described in earlier frameworks such as Mindset Metrics, Struggle as Strategy, and The Silent Signals of Organizations. Across settings, the consistent theme is erosion…erosion of clarity, judgment, cognitive capital, and relational capacity.

First, cognitive narrowing reduces the ability to interpret complexity. Under pressure, individuals revert to familiar strengths. Analysts overanalyze. Operators accelerate execution. Collaborators seek consensus. These behaviors are not failures; they are stress responses. But in environments where complexity demands range, narrowing becomes consequential.

Second, judgment substitution occurs when individuals rely too heavily on AI-generated outputs. The speed of technological recommendations can obscure the need for interpretive reasoning. Over time, the habit of interrogation weakens, and individuals may adopt solutions without examining assumptions or implications.

Third, cognitive capital declines when individuals do not actively engage their full cognitive range. Passive consumption, whether through information overload or overreliance on tools, reduces the depth and endurance of thinking. Memory, creativity, and problem-solving diminish not because they are lost, but because they are underutilized.

Fourth, emotional fragility increases when individuals lack reliable practices for regulating stress. Without the ability to stabilize the nervous system, cognitive access remains compromised. The result is not incompetence but inconsistency.

Finally, individuals lose meaning-making capacity. With data exceeding human bandwidth, the challenge becomes determining what matters. Without intentional reflection, individuals become directionally disoriented even as they grow more technically capable.

These risks are not personal shortcomings; they are structural consequences of a rapidly shifting environment. Yet they are avoidable with deliberate practice.

How Individuals Expand Cognitive Range

The development of integrative intelligence does not depend on innate preference. It depends on intentional practice aligned with the mechanisms of human cognition.

Movement-based learning supports neural integration by engaging hemispheric coordination and improving access to higher reasoning. Cross-disciplinary exploration exposes the mind to new patterns, expanding conceptual scaffolding. Stress-regulation practices preserve cognitive flexibility under pressure, enabling individuals to think broadly rather than reactively. Reflective practices such as journaling, structured inquiry, and metacognition help individuals surface assumptions and examine internal narratives. Exposure to unfamiliar environments strengthens adaptability by challenging existing mental models, such as journaling, structured inquiry, and metacognition, help individuals.

These methods are neither remedial nor supplementary; they are foundational for cognitive expansion in a high-velocity environment. They enable individuals to participate fully in the Expansion Era, where the capacity to adapt, interpret, and integrate will define long-term relevance.

“Cognitive range, not specialization, determines adaptability in accelerated environments.”

Why Leaders Carry a Parallel Responsibility

While individuals must expand their thinking, leaders must expand the conditions that support it. The earlier article The Cognitive Strategy of Leadership introduced the idea that leaders do not merely guide decisions; they shape cognitive environments. Every system either widens or restricts cognitive range. Workload design, communication architecture, feedback loops, and decision structures all influence the amount of mental bandwidth individuals have.

Leaders who overlook these dynamics risk unintentionally weakening the very capabilities their organizations rely on. Cognitive overload accelerates narrowing. Ambiguity without support creates reactivity. Cultures that reward speed over reflection diminish judgment. Environments that underinvest in belonging erode psychological stability, reducing cognitive access.

Leadership in the Expansion Era, therefore, requires two simultaneous responsibilities: managing external strategy and managing internal mindsets.Moorhouse+Group The latter is a direct extension of the previously introduced mental fitness principles. Individuals perform best when clarity, energy, trust, and belonging are supported systematically. Leaders who cultivate such environments ensure that integrative intelligence is not a personal advantage but an organizational one.

In this sense, leaders must become architects of cognitive ecosystems. Their task is not to remove complexity, but to ensure individuals possess the cognitive bandwidth necessary to navigate it.

The Organizational Implications of Integrative Intelligence

The shift toward integration affects every element of organizational design.

Hiring must prioritize cognitive range, not just technical depth. Development programs must emphasize adaptability, not static competency frameworks. Work design must reduce unnecessary cognitive load and increase opportunities for exploration, reflection, and cross-functional exposure. Performance evaluation must incorporate judgment quality, meaning-making, and the ability to interpret complexity. Strategic planning must acknowledge that the most significant risk is not technological disruption but human underpreparedness.

Organizations that recognize this shift early will strengthen their resilience. Those who cling to outdated models of expertise risk becoming increasingly fragile… technically advanced but humanly diminished.

“The leaders who thrive in the Expansion Era will be those who actively cultivate integrative intelligence. First in themselves, then in their organizations. The question is not whether the world will accelerate. It will. The question is whether you will expand with it.”

- Arnsten, A. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function.

- McEwen, B. (2013). The Brain on Stress.

- Pascual-Leone, A. (2005). The plastic human brain cortex.

- Voss et al. (2013). Exercise, brain, and cognition across the lifespan.

- Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- Hogarth, Robin. Educating Intuition.

- Klein, Gary. Sources of Power.

- Barsalou, L. (2008). Grounded cognition.

- Oppezzo & Schwartz (2014): walking increases creative output.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik & McAfee: The Second Machine Age

- NBER Working Paper (2023): Generative AI enhances novice worker performance

- Edmondson, Amy: psychological safety & cognition

- Weick: sensemaking

- Daniel Pink (2004): A Whole New Mind