Why Faster, Cheaper Automation Is Making Change Harder to Absorb

The Paradox Leaders Are Experiencing but Struggling to Name

Over the last several years, a quiet tension has been building inside organizations.

Leaders are investing heavily in automation. The tools are better than ever, faster to deploy, easier to use, and far less expensive than they once were. From workflow platforms to AI-driven decision support, the promise is compelling: greater efficiency, improved performance, and a more scalable organization.

Yet many leaders are noticing something that doesn’t quite align with that promise.

Adoption is uneven. Engagement fades soon after rollout. Teams comply, but don’t fully commit. Workarounds emerge. Old habits resurface under pressure. Resistance, when it appears, is rarely loud. More often, it is subtle and difficult to confront.

This is not the resistance of the past. It is quieter, harder to detect, and easier to misinterpret.

The prevailing explanation is often unsatisfying. If the technology works and people are capable, the issue must be execution, communication, or mindset. Leaders respond by refining change plans, accelerating timelines, or adding more training. In many cases, the result is more effort with diminishing returns.

What if the issue isn’t execution at all?

What if the problem isn’t the technology, or the people, but the interaction between the pace of modern automation and the limits of human systems?

This is the paradox many organizations are now living inside: as automation improves, adoption often becomes harder, not easier. Until leaders name that paradox clearly, they will continue to push on the wrong levers.

What This Means for Leaders

The implications of the Automation–Adoption Paradox are not primarily technical. They are cognitive and human.

Most leadership teams are now capable of changing faster than their organizations can absorb. This gap explains why many transformations feel successful on paper but unstable in practice.

Leadership, in this environment, requires a shift in orientation.

The question is no longer how quickly change can be executed. It is how intentionally change is designed for absorption, through cadence, consolidation, and capacity.

Cognitive and emotional resources must be treated as operational constraints. Attention, learning capacity, and emotional bandwidth shape performance as directly as capital and infrastructure.

The future advantage will not belong to the organizations that move the fastest. It will belong to those that align the pace of change with the capacity of their people.

Progress That People Can Absorb

Automation is not the enemy. Speed is not the villain.

What has changed is the context in which progress must now occur.

As automation becomes cheaper and more accessible, the limiting factor shifts from capability to capacity. Not technological capacity, but human capacity, the ability to integrate, adapt, and perform consistently amid constant change.

The Automation–Adoption Paradox offers language for this reality without blaming people or rejecting progress. It reframes adoption as a systems design challenge rather than a motivation problem.

Progress that outpaces human absorption is fragile. Progress designed around it becomes enduring.

The organizations that thrive in the next phase will not be the ones that automate the most. They will be the ones that design change people can actually absorb.

What Changed: Automation Got Cheap, and Change Accelerated

The economic side of this story is well understood.

Over the past two decades, the cost of automation has fallen dramatically. Compute power is cheaper and more accessible. Software has shifted from capital-intensive builds to modular, subscription-based services. Development barriers have been lowered through APIs, low-code platforms, and increasingly, AI-assisted tools.

Automation is no longer rare, expensive, or centralized. It is now operational, easy to initiate, quick to modify, and painless to replace.

This shift has changed not only what organizations can do, but how often they choose to do it.

When automation becomes cheaper and easier to deploy, organizations naturally experiment more. Systems are updated more frequently. Processes are reconfigured continuously. Tools are replaced before previous ones have fully settled. What once required careful planning and long-term commitment now feels reversible and low risk.

The unintended consequence is not less disruption, but more of it.

“Lower cost does not reduce disruption. It multiplies it.”

This pattern aligns with research on digital acceleration and productivity, including work by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, as well as recent analysis from McKinsey and MIT Sloan on continuous transformation.

Change no longer arrives as a distinct event. It arrives as a constant stream.

This pattern is visible across industries, but it is especially pronounced in environments where regulation, competition, and customer expectations intersect. Mortgage banking is one example, where rate volatility, regulatory shifts, product complexity, and technology upgrades collide in ways that demand continuous adjustment from both internal teams and external partners.

But this is not a tech industry-specific phenomenon. Similar dynamics appear in healthcare, financial services, logistics, professional services, and technology itself. Automation is now embedded not only in internal workflows, but in customer-facing systems, partner integrations, and decision-making processes.

As a result, change pressure is no longer confined to IT or operations. It ripples outward, affecting entire ecosystems.

Employees must learn new tools continuously. Customers adapt to evolving interfaces and processes. Partners adjust to shifting integrations and expectations. Stability becomes elusive, not because organizations are failing, but because the environment no longer allows it.

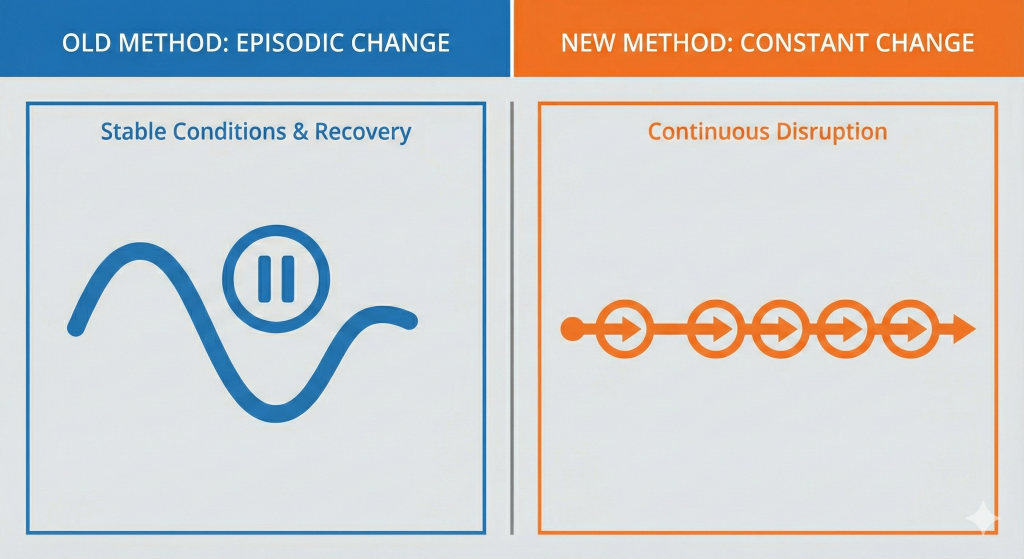

From Episodic Change to Perpetual Change Management

For decades, most change models shared a common assumption: change was episodic.

Organizations operated in stable conditions punctuated by periods of transformation. A system was implemented. A process redesigned. A reorganization completed. Disruption followed, but eventually, things settled. People adapted. Performance stabilized. Confidence returned.

That recovery phase mattered more than leaders often realized.

Recovery is where learning consolidates. It is where people move from surface familiarity to genuine competence. It is where new behaviors become habits and new systems become trusted. Without recovery, change remains fragile.

Today, that phase has disappeared.

Many organizations now operate in a state of perpetual change management. Initiatives overlap. Systems update continuously. Processes are refined before earlier versions have fully integrated. There is little pause, and even less consolidation.

Technical systems can tolerate this environment. Human systems cannot.

Humans require periods of cognitive consolidation to integrate learning. This reflects well-established findings in areas such as cognitive load theory and working-memory research, which show that learning degrades when new demands arrive faster than they can be integrated.

They need time to make sense of new information, rebuild confidence, and regain a sense of mastery. When those periods are removed, learning degrades, not because people are unwilling, but because capacity is exceeded.

Adoption, in this context, becomes superficial. People are exposed to new tools, but they do not fully internalize them. They know of the system, but do not trust it. They can navigate it under ideal conditions but revert under pressure.

This is not a failure of motivation or intelligence. It is a predictable response to sustained overload.

The critical shift most organizations have missed is this: we have optimized for the speed of change without accounting for the speed of human absorption. That gap is where the Automation–Adoption Paradox begins to take shape.

Why Adoption Looks Easier, but Often Isn’t

On the surface, it would be reasonable to assume adoption should be improving.

Employees today are more digitally fluent than at any point in history. They are accustomed to regular updates, new applications, and evolving interfaces in their personal lives. Enterprise tools are also undeniably better designed, more intuitive, more visual, and easier to access. Culturally, change itself has become normalized. Few organizations expect long periods of stability anymore. “We’re always changing” has become a common refrain.

Taken together, these signals create a powerful, and misleading, assumption: that people are more ready for change than ever before.

These conditions reduce initial friction, not sustained adoption.

Digital fluency helps people get started, but it does not guarantee depth of understanding. Intuitive interfaces shorten onboarding, but they do not eliminate the need to unlearn old habits or rebuild confidence. Cultural acceptance of change may reduce overt resistance, but it does not ensure engagement, commitment, or trust.

The mistake many leaders make is subtle but consequential. They confuse familiarity with change for capacity to absorb it.

Learning science draws a clear distinction between exposure and transfer, between recognizing something and being able to apply it reliably under pressure.

Familiarity means people recognize the pattern. Capacity means they can integrate it, make sense of it, and perform reliably under pressure. The two are not the same.

As a result, organizations increasingly experience a hollow form of adoption. Systems are used but not fully embraced. Features exist but are bypassed. Compliance is visible, but confidence is not. Under ideal conditions, performance appears acceptable. Under stress, old behaviors return.

This is why modern resistance is so difficult to diagnose. It rarely looks like refusal. More often, it looks like hesitation, quiet workarounds, partial engagement, or teams doing just enough to get by.

What leaders often interpret as a motivation or mindset problem is something else entirely: saturation.

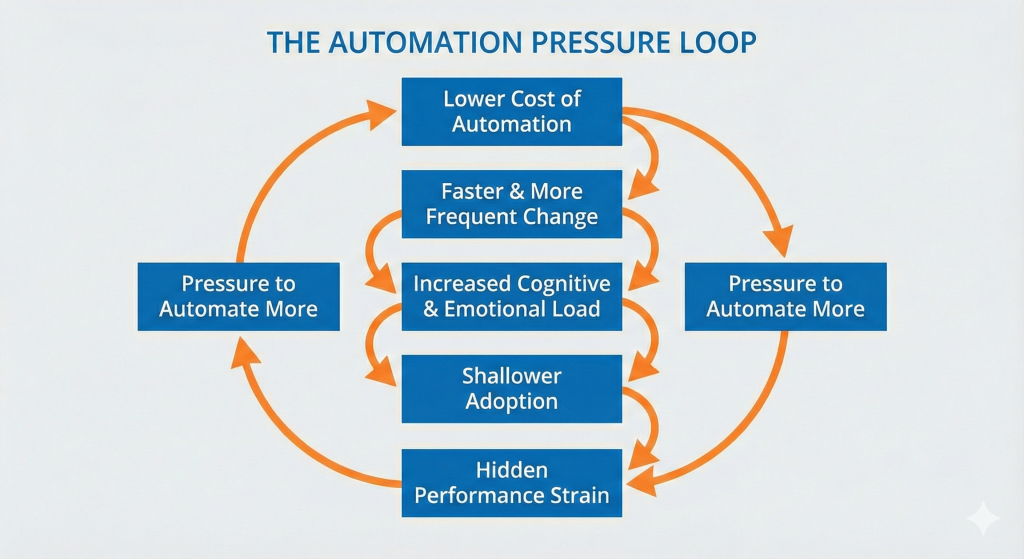

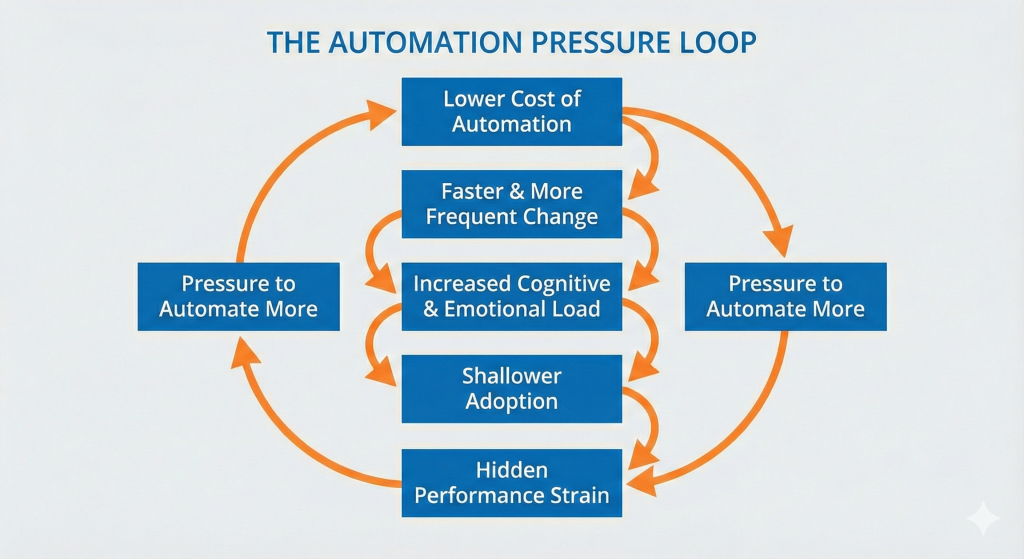

The Automation–Adoption Paradox

This is where the tension becomes clear.

As automation has become cheaper, faster, and easier to deploy, the frequency of change has increased dramatically. Individual changes may be smaller, more intuitive, and less disruptive than in the past. Collectively, however, they accumulate.

The result is a paradox many organizations now face but rarely name: This is the Automation–Adoption Paradox.

The same forces that make automation more effective are making adoption harder to sustain.

As the pace of automation accelerates, it collides with a fixed constraint: human cognitive and emotional capacity.

The paradox is not that people resist technology. It is that human systems have limits. Attention is finite. Learning capacity is constrained. Emotional bandwidth, especially under sustained uncertainty, is easily depleted. When change arrives faster than these systems can absorb, adoption degrades, even when the tools themselves improve.

This degradation is not linear. It is cumulative.

“We’ve optimized for the speed of change without accounting for the speed of human absorption.”

Each new system introduces new rules, workflows, exceptions, and mental models. Even incremental changes stack. Over time, this accumulation produces decision fatigue, erodes confidence, and increases reliance on shortcuts. People may remain capable, but they are no longer grounded.

From the outside, the organization appears to be moving forward. Systems are live. Dashboards are active. Timelines are met. Beneath the surface, however, integration is shallow. Mastery is incomplete. Trust is fragile.

This explains why organizations can appear digitally advanced while feeling operationally strained.

The paradox also clarifies why traditional responses to adoption challenges fall short. More training addresses knowledge gaps, not cognitive overload. Better communication clarifies intent but does not restore capacity. Faster rollouts reduce disruption windows but eliminate recovery time.

What is missing from most change conversations is not urgency or commitment. It is an honest accounting of absorption.

In an era of perpetual change management, the critical leadership question is no longer How quickly can we implement? It is How much change can our people actually integrate, right now, without degrading performance?

What Resistance Really Is Now

When leaders talk about resistance, they often imagine a familiar picture: pushback, complaints, open skepticism, or refusal to comply. In many organizations today, that picture is increasingly rare.

Resistance has not disappeared. It has changed form.

Research on psychological safety, including work by Amy Edmondson, helps explain why resistance increasingly shows up as silence or withdrawal rather than open opposition.

Modern resistance is quieter, more subtle, and easier to misread. It shows up as hesitation rather than opposition. As partial engagement rather than refusal. As teams that comply on the surface but revert under pressure. As systems that are technically in use but not fully trusted.

This kind of resistance is difficult to confront because it does not announce itself. There are no loud objections to address, no obvious blockers to remove. From a distance, everything works.

What leaders are often seeing is not defiance, but self-protection.

Will I still be competent? Will I still be relevant?

Repeated change places people in a vulnerable position. Each new system asks them to relearn work they may have previously mastered. Each update carries an implicit risk: Will I still be competent? Will I still be relevant?

When people sense that mastery is constantly being reset, they begin to conserve energy. They limit how deeply they invest. They learn just enough to function, but not enough to fully commit. They stop experimenting. They rely on familiar workarounds. They defer judgment to the system rather than engaging with it.

This is not a lack of motivation. It is a rational response to sustained uncertainty.

The irony is that leaders often interpret this quiet resistance as progress. Complaints have decreased. Rollouts are smoother. Timelines are met. Beneath that surface calm, engagement has thinned.

What looks like acceptance is often withdrawal.

Adoption Debt: The Hidden Accumulation Leaders Don’t See

Another consequence of accelerated change rarely appears in dashboards or post-implementation reviews.

It accumulates slowly. It hides in plain sight. Over time, it becomes expensive.

This is adoption debt.

The idea parallels Ward Cunningham’s original description of technical debt, not as failure, but as deferred investment that eventually comes due.

As organizations introduce new systems more frequently, they rarely retire the old cognitive demands that came with previous ones. Learning is deferred rather than completed. Integration is partial rather than deep. People move on to the next initiative before mastery of the last is achieved.

Individually, these compromises seem manageable. Collectively, they add up.

Adoption debt forms when organizations mistake exposure for integration. People attend training, log in, and complete basic tasks, but do not fully internalize new ways of working. They lack confidence in edge cases. They struggle when conditions change. They rely increasingly on rules, scripts, and escalations rather than judgment.

Like technical debt, adoption debt is invisible, until it isn’t.

It surfaces as declining performance despite increased tooling. As rising error rates in complex situations. As teams that appear busy but feel brittle. As organizations that move quickly but struggle to adapt under stress.

“Organizations don’t fail at adoption because people resist change. They fail because change arrives faster than people can integrate it.”

Most importantly, adoption debt erodes trust, both in systems and in leadership. When people sense that change is continuous, but learning is optional, they adjust their behavior accordingly. They preserve energy. They wait out the next change rather than fully embracing the current one.

Organizations that appear highly automated but fragile have often optimized for deployment, not absorption.

When Adoption Actually Improves, and Why Speed Sometimes Helps

The Automation–Adoption Paradox does not argue for slowing innovation indiscriminately. There are moments when speed improves adoption rather than undermines it.

The difference lies not in velocity alone, but in what that velocity does to cognitive load.

Adoption improves when change clearly removes friction people already experience. When a new system eliminates manual work, reduces ambiguity, or resolves persistent points of failure, people lean in. The value is immediate and felt, not abstract or deferred.

Adoption also improves when psychological safety is present, when learning curves are expected, mistakes are survivable, and competence is not publicly threatened. In these environments, people invest more deeply. They explore. They integrate new tools into how they think, not just how they execute.

Crucially, adoption improves when change reduces total cognitive demand. The most successful transformations replace complexity rather than layering on top of it. They retire old rules, remove redundant workflows, and simplify decision-making.

Visible leadership modeling matters as well. When leaders use the tools themselves and struggle openly, they signal that mastery is built, not assumed.

Under these conditions, speed creates momentum rather than exhaustion. Absent them, acceleration compounds strain.